There has been an interest in attorney fees in Florida workers' compensation, seemingly as long as I can remember. My history in this industry certainly is not even close to that of some of our community icons, a handful of whom have remained in this practice since the late 1960s and early 1970s. However, I recall discussions of fees throughout much of my career.

Some historical overviews may be helpful. Workers' compensation came to Florida in 1935 in Chapter 5966. The Florida community today readily short-hands its "comp" references to "440," the statutory current home of our workers' compensation law. Many do not realize that is not the statute chapter in which comp originally resided. The original statute included a very brief section on attorney fees; it essentially said any fees had to be approved by the "commission." As an aside, some readers may not realize that most of the Florida workers' compensation laws are available in PDF on the "resources" tab of the OJCC website.

Over time, statutory provisions regarding fees were defined and constrained. The word "reasonable" was added, as was a provision affording a fee avoidance (if benefits are provided within 21 days). The Florida Supreme Court weighed in back in 1968 with Lee Engineering v. Fellows, 209 So.2d 454 (April 10, 1968), judicially legislating 6 factors relevant to a determination of "reasonable." The separation of powers discussions that can involve Fellows are intriguing.

In the 1970s a claimant fee formula (percentages) was added, a process for splitting fee liability among employee and employer, and eventually, a "bad faith" fee standard was codified. Later years brought a thirty-day window for employers to provide claimed benefits without fee liability, and adjustments to the formula fee, which had become colloquially known as the "statutory fee" in common parlance.

The Lee Engineering "factors" were codified, more than once modified, and interpreted. What had been a "presumptive" fee formula purportedly became mandatory in 2003. Litigation ensued, and in 2008 Murray v. Mariner Health, 994 So.2d 1051 (Fla. 2008)(October 23, 2008) clarified that the formula remained suggestive but not binding. That effort at statutory construction was seen as strained by some. The legislature in 2009 rendered the formula mandatory again. That set the stage for more litigation, and 2016 brought the decisions of the First District in Miles v. City of Edgewater Police, 190 So.3d 171 (Fla. 1st DCA 2016)(April 20), and the Florida Supreme Court in Castellanos v. Next Door Company, 192 So.3d 431 (Fla. 2016)(April 28).

As screenwriter and director Dee Rees once said "History informs where we are and how we got here." The foregoing is admittedly brief, certainly cursory, and admittedly merely an overview of history. But, it is perhaps an acceptable "nutshell" version of "how we got here," and find ourselves again discussing Florida attorney fees in 2018. This post will focus on what Office of Judges of Compensation Claims data demonstrates regarding attorney fees. Future posts will focus on other statistical reporting, including petition volumes and more.

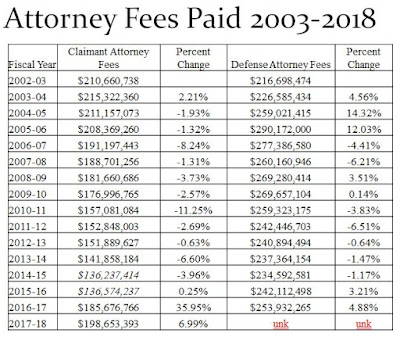

Castellanos and Miles were each decided late in 2016 (Florida operates on a fiscal year, which ends each June 30. Thus, it is possible that these two 2016 decisions impacted 2016 statistics, but only late, in the last 60 to 70 days of that year. Anecdotally, there were those who claimed to have postponed attorney fee agreements or claims in 2016, awaiting or anticipating appellate court decisions. Thus, there is some belief that a "reservoir" of claims had accumulated by the time the two appellate decisions were rendered. The aggregate of claimant attorney fees awarded and approved in 2016 were very consistent with those in 2015.

Some historical overviews may be helpful. Workers' compensation came to Florida in 1935 in Chapter 5966. The Florida community today readily short-hands its "comp" references to "440," the statutory current home of our workers' compensation law. Many do not realize that is not the statute chapter in which comp originally resided. The original statute included a very brief section on attorney fees; it essentially said any fees had to be approved by the "commission." As an aside, some readers may not realize that most of the Florida workers' compensation laws are available in PDF on the "resources" tab of the OJCC website.

Over time, statutory provisions regarding fees were defined and constrained. The word "reasonable" was added, as was a provision affording a fee avoidance (if benefits are provided within 21 days). The Florida Supreme Court weighed in back in 1968 with Lee Engineering v. Fellows, 209 So.2d 454 (April 10, 1968), judicially legislating 6 factors relevant to a determination of "reasonable." The separation of powers discussions that can involve Fellows are intriguing.

In the 1970s a claimant fee formula (percentages) was added, a process for splitting fee liability among employee and employer, and eventually, a "bad faith" fee standard was codified. Later years brought a thirty-day window for employers to provide claimed benefits without fee liability, and adjustments to the formula fee, which had become colloquially known as the "statutory fee" in common parlance.

The Lee Engineering "factors" were codified, more than once modified, and interpreted. What had been a "presumptive" fee formula purportedly became mandatory in 2003. Litigation ensued, and in 2008 Murray v. Mariner Health, 994 So.2d 1051 (Fla. 2008)(October 23, 2008) clarified that the formula remained suggestive but not binding. That effort at statutory construction was seen as strained by some. The legislature in 2009 rendered the formula mandatory again. That set the stage for more litigation, and 2016 brought the decisions of the First District in Miles v. City of Edgewater Police, 190 So.3d 171 (Fla. 1st DCA 2016)(April 20), and the Florida Supreme Court in Castellanos v. Next Door Company, 192 So.3d 431 (Fla. 2016)(April 28).

As screenwriter and director Dee Rees once said "History informs where we are and how we got here." The foregoing is admittedly brief, certainly cursory, and admittedly merely an overview of history. But, it is perhaps an acceptable "nutshell" version of "how we got here," and find ourselves again discussing Florida attorney fees in 2018. This post will focus on what Office of Judges of Compensation Claims data demonstrates regarding attorney fees. Future posts will focus on other statistical reporting, including petition volumes and more.

Castellanos and Miles were each decided late in 2016 (Florida operates on a fiscal year, which ends each June 30. Thus, it is possible that these two 2016 decisions impacted 2016 statistics, but only late, in the last 60 to 70 days of that year. Anecdotally, there were those who claimed to have postponed attorney fee agreements or claims in 2016, awaiting or anticipating appellate court decisions. Thus, there is some belief that a "reservoir" of claims had accumulated by the time the two appellate decisions were rendered. The aggregate of claimant attorney fees awarded and approved in 2016 were very consistent with those in 2015.

In 2017, however, the aggregate increased about $49M, which was almost 36%. Since that increase was published, many have wondered or prognosticated aloud regarding whether that increase represented the resolution of some portion of the purported "reservoir" or perhaps portended a trend to increase. The answer to that perhaps lies in future data compilation and evaluation of whether the trend to increase continues. Some may argue that the more modest 2018 increase, a moderation of the trend to increase, supports the "reservoir" supposition.

In 2018, the aggregate claimant attorney fees in Florida increased another almost $14M, almost 7%. Caveat, these figures are aggregated and calculated in the process of preparing the statutory annual report each fall. Much work remains in that process, and these figures are subject to change as audit processes continue. The figures in the chart above for both 2015 and 2016 (italics) were slightly adjusted this year when minor accounting errors were corrected.

In sum, aggregate claimant fees in Florida continued an upward trend in 2018. Some may point out that 7% is far different from 36%. Others may comment that 7% is significant and might cite recent news that a 4.1% rate of growth in American domestic product ("GDP") was hailed as significant by various commentators. Still others may reference that aggregate claimant fees in 2017, despite that $49M increase, remained about $68M less than aggregate defense fees. And, a few will question why 2018 defense fees are not included in this post (defense fee reporting for 2018 will not close until September (Rule 60Q6.124(6)), and unfortunately final calculations are not usually completed until October.

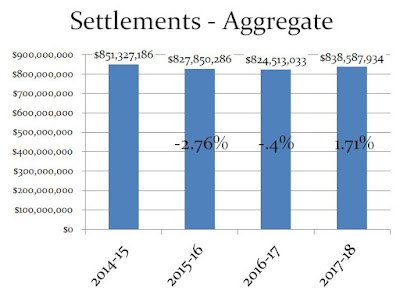

There is some notable consistency in the 2018 data compared to the data for the previous three years. One example is the aggregate paid in approved settlements. Those figures have been notably consistent.

Most settlements of workers' compensation benefit entitlement will be known to the Office of Judges of Compensation Claims. There is the potential, however, for certain entitlements for those represented by counsel to be addressed through other agreements, as discussed in Patco Transport, Inc. v. Estupinan, 917 So.2d 922 (Fla. 1st DCA 2005); but see Cabrera v. Outdoor Empire, 108 So.3d 691 (Fla. 1st DCA 2013) regarding unrepresented workers and waiver of benefit entitlement. I am periodically surprised in discussions when attorneys express unawareness of the potential Estupinan impact.

Similarly, there is fluctuation in the number of settlements approved each year, but the trend is also similarly one of notable consistency. This is also subject to the same Estupinan caution.

Similarly, there is fluctuation in the number of settlements approved each year, but the trend is also similarly one of notable consistency. This is also subject to the same Estupinan caution.

Thus, the number of settlement orders being entered (whether approving fees and child support - where the worker is represented, or approving the actual settlement - where the worker is not) has varied. However, there is notable consistency year after year. For clarity, the graph above depicts "represented settlement volume." The figures for unrepresented settlements, however, are similarly consistent: 2015 - 1,478; 2016 - 1,359; 2017 - 1,379; 2018 - 1,356.

The 2018 data thus far demonstrates notable consistency regarding the volume and aggregate dollar value of Florida settlements. The aggregate value of claimant attorney fees increased in 2018 for the second consecutive year, post-Castellanos and Miles. The rate of increase has moderated, but may nonetheless be characterized as "significant" by some. The claimant fee aggregate for 2018, despite two years of increase, remains significantly below the defense fee aggregate for 2017 (calculations later this fall will perhaps provide further perspective).