The 2019 OJCC Annual Report is nearing completion. It will be published before December 1. It will be posted on the OJCC website (www.fljcc.org) at that time. This report is 250+ pages of pure reading enjoyment (though it might also put you to sleep if you try to take it all in at once).

An issue that generates multiple questions every fall seems to be "What were the attorney fees?" As the report is in its final proofing, this post will share the answer to that specific question.

Note that Claimant fees are documented and recorded when orders are signed to approve them. The data is dependent upon the lawyers who complete those affidavits and fee data sheets for accuracy. Thus, it is possible for a fee to be labeled as a "percentage" or an "hourly" fee by the attorney receiving the fee. Unless the assigned judge makes a specific finding to contradict such characterizations, the data collection process relies on the attorney representation(s). Defense fees are reported in aggregate total by the company that paid them (thus we do not collect how much was spent by "ABC" Insurance on each case, merely how much ABC overall spent on defense fees).

During 2018-19, a total of four hundred seventy-three million nine hundred thirty-seven thousand and thirty-one dollars ($473,937,031) was paid in combined claimant attorneys’ fees and defense attorneys’ fees (and perhaps defense “costs”) in the Florida worker’s compensation system. This represents a small increase, about 5%, from the 2017-18 aggregate fee total of four hundred fifty-three million one hundred seventy-nine thousand one hundred ninety-one dollars ($453,179,191) in 2017-18. The aggregate attorney fee total for the system has increased in each of the last four fiscal years.

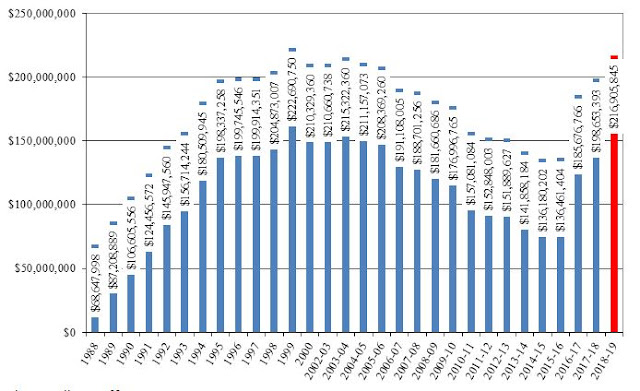

The 2016-17 increase in fees following Castellanos v. Next Door Company, 192 So. 3d 431 (Fla. 2016) and Miles v. City of Edgewater, 190 So. 2d 171 (Fla. 1st DCA 2016) was significant and was seen as supporting that further fee total increases were likely. The continued increases in 2017-18 and 2018-19 support that hypothesis. The 2018-19 increase of 9% resulted in the highest claimant attorneys’ fee total ($216,905,845) since the 2003 amendments to the Florida workers’ compensation law.

The aggregate attorneys’ fees in Florida workers’ compensation was close to a 50/50 distribution in 2002-03, but aggregate claimant fees decreased and employer/carrier fees first increased markedly and then decreased at a more moderate pace, resulting in a significant disparity between claimant and defense fees. Beginning in 2009-10, the defense portion exceeded 60% for seven years, peaking at almost 64% in 2015-16. However, the significant increase in claimant fees in 2016-17, followed by notable growth in 2017-18 (7%) and 2018-19 (9%), and comparatively nominal growth in defense fees in those two years (less than 1%) has markedly decreased the defense fee percentage. Despite that, the defense fees remain in excess of 54% in 2018-19. Over the sixteen years since the 2003 legislative reforms, claimant fees are currently up about 3% overall and defense fees are up about 19%.

The notable increase in claimant attorneys’ fees in 2016-17 was mostly attributable to hourly attorneys’ fees for litigation of issues. The marked increase in 2017-18 and 2018-19 was instead attributable to claimant-paid attorney fees related to settlements.

The Department of Labor and Employment Security (“DLES”) compiled data regarding the attorneys’ fees paid to claimants’ counsel for a number of years. In the DLES 2001 Dispute Resolution Report, fees for calendar years 1988 through 2000 were reported. These figures are accepted at face value. According to the data including these DLES figures, claimant fees in 2019 (aggregate) were the second-highest total since 1988. Notably, there has been significant inflation over those years, and the inflation-adjusted figures might tell a different story.

Despite that, these figures are helpful for broad comparisons with current fees and trends. Notably, the DLES figures (1988-2001) for claimant attorneys’ fees likely include costs, as the ability to easily differentiate fees from costs did not exist until the OJCC database was deployed in 2002.

The Castellanos effect:

The effects of the Castellanos decision were apparent in the 2016-17 attorney fee figures (non-settlement, hourly fees in green below). Claimant’s fees increased overall by 36.07% that year. The majority of that increase was in the category of “non-settlement hourly” fees. That category (likely E/C-paid) increased from $25,866,295 in 2015-16 to $75,353,918 in 2016-17, an increase of almost $50 million (+191%). By comparison, there was a much less significant increase in the settlement fees (likely Claimant-paid) from $94,422,559 in 2015-16 to $99,066,123 in 2016-17, an increase of about $4.5 million (+5%).

The Miles Effect

The effects of Miles (settlement fees in blue above) were comparatively less apparent in 2016-17, but are illustrated better in 2017-18 and 2018-19. In 2017-18, the “non-settlement hourly” fees (Castellanos) decreased from $75,353,918 in 2016-17 to $70,013,393 (-7%); in 2018-19, there was some increase in that total ($71,584,645; 2%. However, the settlement fees (Miles) increased from $99,066,123 in 2016-17 to $118,069,209 (+19%) in 2017-18; the increase continued at a similar pace (+18%) up to $139,343,544 in 2018-19. Such an increase might be explained by a greater volume of represented settlements, a higher value of those settlements (upon which the fee is calculated), or a greater portion of those settlements being paid in fees.

The data does not support that the aggregate value of settlements increased significantly in 2017-18 (+1.71%), as illustrated in the graph below; as the settlement fees increased 18% in 2018-19, the aggregate settlement dollar value decreased slightly (.33%). In sum, the total aggregate of dollars in represented settlements has also not demonstrated significant change. The changes were: 2015-16 (-2.8%), 2016-17 (-.4%), 2017-18 (1.7%), and 2018-19 (-.33%). The figures for each of the last five fiscal years are illustrated below.

The volume of represented settlements likewise has not changed significantly. The changes were: 2015-16 (2.2%), 2016-17 (-1.1%), 2017-18 (.5%), and 2018-19 (1.6%).

Thus, the increase in settlement fees seems appropriately attributed primarily to Miles, though some may propose other causes. As of this writing, no other explanation has been proposed. That case has been interpreted by some as allowing claimant-paid fees to exceed the statutory formula in section 440.34(1), Florida Statutes without demonstration of case-specific constitutional infirmity or implication.